Why is Seattle Still Segregated? Realtors, Banks and Developers Played a Role

The practice was called “red lining,” but it wasn’t really a red “line” that kept families of color out of most neighborhoods in Seattle. It was an area on a map that was colored red. It delineated the portions of a city that were too risky for the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to insure mortgages at its inception as a New Deal Program in 1933. Eighty-eight years later, red lined neighborhoods still reflect their segregated legacy.

The practice was called “red lining,” but it wasn’t really a red “line” that kept families of color out of most neighborhoods in Seattle. It was an area on a map that was colored red. It delineated the portions of a city that were too risky for the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to insure mortgages at its inception as a New Deal Program in 1933. Eighty-eight years later, red lined neighborhoods still reflect their segregated legacy.

RARE committee member Jude Fisher shared the history of red lining in Seattle at a February RARE discussion session to help the group understand why Seattle is still segregated. In our blog article “How did we get this way? Why Seattle remains segregated”, we examined how restrictive neighborhood covenants helped shape the make-up of neighborhoods. But covenants alone didn’t cause the separation between white families and families of color.

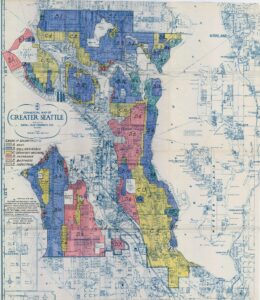

Fisher shared a 1930s-era map of Seattle that showed marked red areas, most notably central Seattle south of Madison and West Seattle west of the Duwamish River but east of the Puget Sound view property. The “best” properties were colored green, “still desirable” were blue, and “definitely declining” properties were marked yellow. But it was the areas marked red, or “hazardous,” that were open to families of color.

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) originated mortgage redlining when the agency first started in 1933. Properties in hazardous areas were denied lending and investment services. HOLC’s stated purpose was to refinance home mortgages that were in default, in order to prevent foreclosure and to expand home buying opportunities. A 2020 study in the American Sociological Review found that HOLC led to substantial, persistent racial residential segregation.

Not only were people of color denied mortgages in red lined areas, but developers were not given loans to build housing in those areas. Home owners in those areas could not get home improvement loans, either, which only added to the decline of those neighborhoods.

Fisher explained that the maps were in the Underwriting Manual of the Federal Housing Administration (first publicly available in 1936), which said that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities.” That is, loans to African Americans could not be insured. The FHA justified this policy by holding that if “colored” people bought homes in or near these suburbs, the property values of the insured homes (read: white homes) would decline. Therefore, their loans would be at risk.

The FHA had no basis for the claim.

Redlining was a policy, not a law. But neither was it hidden, so it was not considered “de facto” segregation. Ultimately, it was determined to be unconstitutional, she explained.

The banks were in on it, too. Since FHA loans were less risky, banks lowered the interest rates and used the redline “security” maps to determine who would be approved for a loan and where.

But the discrimination didn’t stop there. The 1930s FHA guidelines placed a condition on builders and developers that none of the new homes could be sold to African Americans. Also, each home had a clause in the deed that prohibited resale or rental to families of color.

Wait – there’s more. Between 1924 and 1950, the Realtor Code of Ethics included a section that read, “A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood.”

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 sought to reverse these practices, but to little avail at first. Loans were still denied based on race.

“It’s as if some of these places have been trapped in the past, locking neighborhoods into concentrated poverty,” said Jason Richardson as quoted in a Wikipedia article about the HOLC. Richardson is director of research at the NCRC, a consumer advocacy group, and was commenting on a 2018 study that found that the redlined areas are still minority neighborhoods. Another study published in 2017 and cited by the same article found that areas deemed high-risk by HOLC maps saw an increase in racial segregation.